Identifying Maternal Depression in the Perinatal Period in Low Socioeconomic Patients

Van De Velde N1, Logan J McClure1*, Jennifer C Gordon1, Owen Phillips1, Pallavi Khanna1, Zoran Bursac1, Roberto Levi D Ancona1,2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, USA

2Southern Illinois University, USA

*Corresponding author: Logan J McClure, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology 853 Jefferson Avenue, Suite E102 Memphis, USA.

Article History

Received: July 22, 2021 Accepted: August 24, 2021 Published: September 02, 2021

Citation: Van De Velde, McClure LJ, Gordon JC, et al. Identifying Maternal Depression in the Perinatal Period in Low Socioeconomic Patients. Int. J.Obst & Gync. 2021;1(1):09‒13. DOI: 10.51626/ijog.2021.01.00002

Abstract

Objective: Perinatal depression affects 1 in 7 women and no ideal screening time has been determined. The objective of this study is to evaluate the optimal time to screen for depression in a high risk, low socioeconomic status population utilizing the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Questionnaire as well as to identify depression risk factors in this period.

Methods: A retrospective chart review from December 2016 until June 2017 of women presenting for prenatal care who took the EPDS at least once. EPDS was administered at the initial obstetrical visit, third trimester visit, immediately postpartum, and the six-week postpartum visit. The ACE questionnaire was performed at least once during the perinatal period.

Results: 146 patients met inclusion criteria. Median age was 25 years and 82% were African American. 50.6% had fewer than six prenatal care visits and median number of visits 5 (Interquartile range 2 to 10 visits) and only 49.6% (N=63) of patients returned to their six-week postpartum visit. No statistical difference (p=0.37) in the incidence of depression was observed at the different time intervals: 34% at initial visit, 25% in third trimester, 20% immediately postpartum, and 31% at the six-week postpartum visit. Of those that screened positive for depression, 18 patients endorsed suicidal or homicidal ideation (37% of those screened positive). Of the comorbidities noted, history of depression was found to be statistically significant toward a positive screen for depression (p=0.01). Incidences of depression were similar throughout the perinatal period suggesting that patients can be safely screened for depression at any time throughout the pregnancy or postpartum period.

Conclusion: Patients with positive ACE scores or history of domestic violence should be screened earlier for maternal depression. These findings would allow for early initiation of treatment especially in low socioeconomic settings where loss to follow-up rates are high.

Keywords: Depression; Screening; Pre/Peri/Postnatal Issues; Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; Pregnancy; Adverse Childhood Experiences; Low Socioeconomic Status

Background

Perinatal depression is defined as depression occurring during pregnancy or the subsequent 12 months following pregnancy [1,2]. Perinatal depression affects 1 in 7 women during the perinatal period [3]. Patients with a history of depression are at an increased risk of symptoms during pregnancy. In fact, the most prominent risk factor for perinatal depression is a history of depressive episodes [4]. It is estimated that 54% of women who have experienced depression prior to pregnancy will experience another episode during pregnancy [5]. Untreated depression during pregnancy can result in an increased risk for fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disease, preterm labor, and placental abruption [6]. Untreated depression during the postpartum period also has significant risk, possibly resulting in newborn neglect and morbidity [6]. Putnick et al. [7] detail that up to 25% of mothers may have an increase in depressive symptoms up to 3 years after giving birth [7].

Thus, in order to circumvent these complications and provide symptomatic aid, it is recommended to treat these patients. Pharmacologic treatment itself is an entirely different topic, as many agents have proven safe for patients during the peripartum period or breastfeeding. This requires weighing the risks and benefits and starting medication at the lowest dose and titrate up to control symptoms and maintain safety for both patient and fetus [8]. In order to recognize these symptoms and illness, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommend screening at least one time during the perinatal period for depression [6]. However, the ideal time to screen for depression during the perinatal period has not been determined. Many validated screening tools can be utilized to screen for postpartum depression including the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Postpartum Depression Screening scale, Patient Health Questionnaire 9, and Beck Depression Inventory. The EPDS is a commonly used screening tool due to its low reading level requirement and ability to be self-administered.

The development of psychiatric disorders during adulthood has been linked to a history of childhood neglect and abuse. Kaiser Permanente and the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention performed a study that found a dose-dependent relationship between the number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and the risk of developing chronic diseases including mental illness(es) later in life. There is also evidence to support that maternal ACEs affect childhood development within the first 12 months, especially relating to communication and motor skills [9]. The ACE Questionnaire is a 10-question scoring method of assessing physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect during childhood. There have been no studies to our knowledge that assess ACEs and their contribution to developing depression in the perinatal period.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the optimal time to screen for depression in a high risk, low socioeconomic status population utilizing the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and the Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire as well as to identify depression risk factors in this period. We hypothesize that screening for depression earlier in the perinatal period will allow for earlier detection of perinatal depression, yielding earlier treatment.

Methods

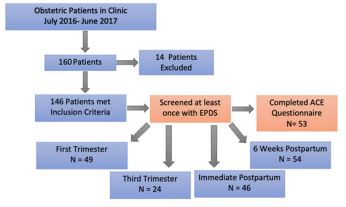

This was a retrospective study of 146 patients who were seen for pregnancy at our academic institution. This study was approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board. We abstracted data for all patients treated for pregnancy at our outpatient center from July 2015 to June 2017. The inclusion criteria ruled in patients that completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) or Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) questionnaires during their pregnancy or postpartum period and completed their delivery at our facility. Patients were excluded from this study if there was insufficient data or if they experienced fetal loss in the first or second trimesters (Figure 1). “Insufficient data” encompasses patients lost to follow up, EPDS without ACE, and too few EPDS.

The EPDS is a common screening tool used to assess postpartum depression. The screening test is composed of 10 questions with a total score that ranges from 0 to 30. A score greater than 10 suggests possible depression and a score greater than 12 suggests depression is likely. Prior to July 2015, the EPDS was routinely provided only at the six-week postpartum visit. Starting July 2015, the screening test was administered at multiple intervals during the perinatal period: first obstetrical visit, third trimester visit, one week postpartum and six-week postpartum visit.

The ACE questionnaire (Figure 1) is composed of 10 questions that assess childhood abuse and neglect. The questionnaire ranges from a score of 0 to 10. The higher the score on the ACE questionnaire, the increased negative health and wellbeing outcomes during adulthood. Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) questionnaire was performed once during the perinatal period [10].

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS. A p-value of <0.05 was considered the threshold of statistical significance. In addition to descriptive statistics, the McNemar test was utilized to compare the administration of EPDS at different time points. The fisher exact test was used to compare risk factors for depression and the Wilcoxon test was used to assess the association between perinatal depression and ACE scores.

Results

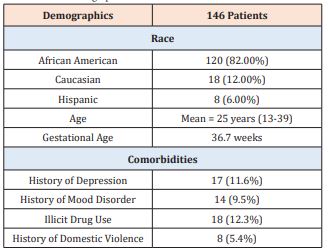

A total of 146 patients met the inclusion criteria. Our patients had a median age of 25 and the range was 13 to 39. The ethnicity composite of the patients included were 82% African American, 12% Caucasian, and 6% Hispanic. The median number of prenatal visits was 6 with an interquartile range of 2 to 10 visits. Fifty-eight percent (N=86) of patients returned to their six-week postpartum visit. Twenty-six percent (N=28) of patients were seen in the Maternal Fetal Medicine clinic for supervision of high-risk pregnancies.

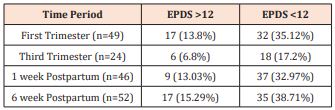

Eighteen percent of patients (N=27) were screened at multiple time intervals during pregnancy, and the remainder of patients were screened only once. Forty-nine patients completed the EPDS at the initial OB visit, 24 during the third trimester, 46 within 1 week of delivery and 54 at the six-week postpartum visit. No statistical difference (p=0.37) in the incidence of depression was observed at the different screening intervals: 34% at initial visit, 25% in third trimester, 20% immediately postpartum and 31% at the six-week postpartum visit (Figure 1). Fifty-three patients completed the ACE questionnaire during the perinatal period. The average ACE score was 1.5 with a range of 0 to 8 points. 19% (N=28) of patients had a history of depression or other mental illness. Of those that screened positive for depression across various time points, 18 patients endorsed suicidal or homicidal ideation (37% of those screened positive). Many had risk factors for depression including history of trauma (N=13), illicit drug use (N=18) or history of domestic violence (N=8). Patients also has medical comorbidities including hypertension (N=11) and pre-gestational diabetes (N=11) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

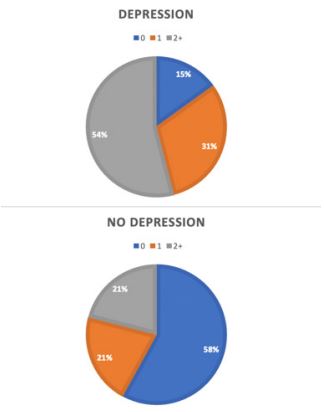

Figure 2: ACE Scores Based on Screening Results.

ACE Scores divided between patients screening positive for depression and those who screened negative. The median ACE score was higher in individuals screening positive for depression. ACE of 1.5 vs. ACE of 1 (p=0.022).

An ACE score of 1 or greater (p-value 0.02) and a history of depression (p-value 0.01) were each associated with a statically significant increased risk of depression in the perinatal period. Mental illness (excluding depression) (p=0.12), illicit drug use (p=0.21) and history of domestic violence (p=0.06) were associated with an increased risk of depression in the perinatal period but were not statically significant (Table 1).

Table 1: Patient Demographics.

The demographic factors for our patient population are shown in Table 1. Of the comorbidities listed, only history of depression was found to be statistically significant toward a positive screen for depression (p=0.01) as opposed to illicit drug use (p=0.21), history of mood disorders (p=0.12), or history of domestic violence (p=0.06).

Discussion

This pilot study is the first to our knowledge to utilize the ACE questionnaire and the EPDS to screen for patients at risk of maternal depression. Our study found that patients who test positive for the ACE score at least once are at an increased risk of maternal depression (p= 0.02), as are those with a history of depression (p= 0.01). We found that there is not an optimal time to screen for maternal depression during pregnancy or the postpartum period, as there is no statistical difference in occurrence of depression at each of our time points (p=0.37). Therefore, patients with an ACE score of one or greater or a history of depression should be screened earlier for depression using one of the validated screening tools. In patients with regular follow up, it is recommended that screening takes place multiple times in both the early and late postpartum periods and possibly as late as 2-3 years postpartum to accurately track the course of the disease and provide adequate treatments [7,11]. Earlier screening would be more beneficial in high risk, low socioeconomic settings as the rate of postpartum follow up is lower (Table 2)¬¬¬¬¬.

Table 2: EPDS Scores at 4 Time Points.

A Chi-squared analysis was performed, and we found that there was no difference in detecting a positive screening for depression at the different time intervals utilizing the EPDS scale, p=0.37

A limitation of this study was the small number of patients that were screened at multiple time intervals for maternal depression at our academic institution. This was largely secondary to patient noncompliance in attending perinatal visits. This noncompliance rate is possibly due to any number of patient factors that present as barriers to care. In patients with lower socioeconomic status there may be lack of transportation to and from medical visits, lack of insurance to pay for visits, inability to pay for visits even with insurance, or difficulty finding childcare. Patients may also prefer peer support, wish to avoid stigma, or simply wish to avoid pharmacologic treatment [12]. Another limitation was that only 36% of patients completed the ACE questionnaire (Figure 3). The ACE questionnaire asks questions that may be difficult for patients to answer honestly. There were at least two patients in our study who refused to answer the questions. As this was a single institution, these results may not be generalizable to other regions.

Figure 3: Sample ACE Questionnaire [12].

There have previously been difficulties discerning which cutoff scores to use on the EPDS to diagnose major depression. Many sources cite a score greater than 11 or “12 or more” as a cutoff, but a single point has been shown to make significant impact in scoring the EPDS [13]. Cox et al. [14] determined that a score greater than 12 was indicative of depressive illness [14]. There is also the possibility of error in scoring by healthcare workers (Figure 4), as there is the potential for variability between different scorers, and Matthey has previously shown that physicians have less accuracy when scoring an EPDS [13].

Figure 4: Sample EPDS Questionnaire [14].

In conclusion, the incidence of depression occurs at similar rates throughout the perinatal period suggesting that patients can be safely screened for maternal depression at any time throughout pregnancy or the postpartum period. Patients who score positive for at least one ACE or those with a history of depression should be screened earlier for depression in the perinatal period. Individuals with a history of domestic violence, mental illness, or illicit drug may be considered candidates for early screening using a validated screening tool. These findings allow for early referral or initiation of treatment for maternal depression especially in low socioeconomic settings where loss to follow up rates may be higher.

Although screening greatly increases the chance of correctly identifying those patients with peripartum depression, there remains the issue of patient follow up and how to best direct their care. Even in states where legislative acts have increased screening, there may not have been a change in initiation of treatment [15]. In fact, only about one in five patients sought further care after screening >10 on the EPDS [12]. In addition, there is evidence to support that pregnant women scoring above the threshold who receive mental health services tend to score lower in the postpartum period [16].

To better treat patients who screen positive, at any point of the peripartum window, future research should investigate potential barriers to medical care to hopefully increase patient follow up and ensure these patients are adequately treated. Further research is also needed to assess women in the perinatal period following the COVID-19 as isolation guidelines and social distancing may worsen any depressive symptoms. Current evidence has found that women have experienced higher levels of stress during childbirth (p= 0.04) and a higher percentage of women have experienced postpartum depression during the pandemic (p= 0.38) [17].

References

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer Brody S, Gartlehner G, et al. (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106(5): 1071-1083.

- Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L (1996) The pathway to care in post-natal depression: women’s attitudes to post-natal depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Pract 46(408): 427-428.

- (2012) Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin 92. Obstet Gynecol 1001-1020.

- Becker M, Weinberger T, Chandy A, Schmukler S (2016) Depression During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Curr Psychiatry Rep 18(3): 32.

- Guo N, Robakis T, Miller C, Butwick A (2018) Prevalence of Depression Among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 131(4): 671-679.

- (2015) Screening for perinatal depression. Committee Opinion No. 630. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 125(5): 1268-1271.

- Putnick DL, Sundaram R, Bell EM, Ghassabian A, Goldstein RB, et al. (2020) Trajectories of Maternal Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. Pediatrics 146(5): e20200857.

- Puryear L, Hall NR, Monga M, Ramin S M (2017) Managing psychiatric illness during pregnancy and breastfeeding: Tools for decision making. OBG Management 29(8): 30-38.

- Racine N, Plamondon A, Madigan S, McDonald S, Tough S (2018) Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Infant Development. Pediatrics 141(4): e20172495.

- Felitti VJ (2002) The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead. The Permanente Journal 6(1): 44-47.

- Putnick DL, Sundaram R, Bell EM, Ghassabian A, Goldstein RB, et al. (2020) Trajectories of Maternal Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. Pediatrics 146(5): e20200857.

- Rowan P, Greisinger A, Brehm B, Smith F, McReynolds E (2012) Outcomes from implementing systematic antepartum depression screening in obstetrics. Arch Womens Ment Health 15(2): 115-120.

- Matthey S, Della Vedova AM, Agostini F (2017) The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in routine screening: errors and cautionary advice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 216(4): 424.

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150: 782-786.

- Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA (2011) New Jersey’s efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 30(2): 293-301.

- Venkatesh KK, Nadel H, Blewett D, Freeman MP, Kaimal AJ, et al. (2016) Implementation of universal screening for depression during pregnancy: feasibility and impact on obstetric care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 215(4): 517.

- Mariño-Narvaez C, Puertas-Gonzalez JA, Romero-Gonzalez B, Peralta-Ramirez MI (2020) Giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact on birth satisfaction and postpartum depression. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 153(1): 83-88.